A Sad, Broken Man

Trump is terrible, but he's also profoundly and irretrievably damaged -- and a figure of both scorn and pity.

If you are a free subscriber and you like what you’re reading, maybe it’s time to upgrade to a paid subscription.

This newsletter is 100% reader-supported, and your subscription helps me continue publishing.

When you become a paid subscriber, you receive access to all my posts, the ability to comment on posts and engage in the Truth and Consequences community, and, above all, you get the warm and fuzzy feeling that comes with supporting independent journalism.

Earlier this week, I wrote that Donald Trump is a “deranged sociopath,” and I stand by that position. Trump is a malignant narcissist, devoid of empathy and introspection, trapped inside a fragile and damaged ego. I’ve joked that Trump is the worst person in America, and though I haven’t met every one of the 330 million people who make up this country, I’m confident in that proclamation.

But this week I was reminded that, as much as I despise Trump, part of me also feels sorry for him.

Here are the two stories that stirred these feelings of empathy

First, the renaming of the Kennedy Center:

The board of the Kennedy Center in Washington voted to rename it the Trump-Kennedy Center, a spokesperson for the arts institution said.

“The unanimous vote recognizes that the current Chairman saved the institution from financial ruin and physical destruction,” Roma Daravi, the center’s vice president of public relations, said in a statement. “The new Trump Kennedy Center reflects the unequivocal bipartisan support for America’s cultural center for generations to come.”

This morning, the signage at the performing arts center was changed to reflect the new name.

Second, “plaque-gate.”

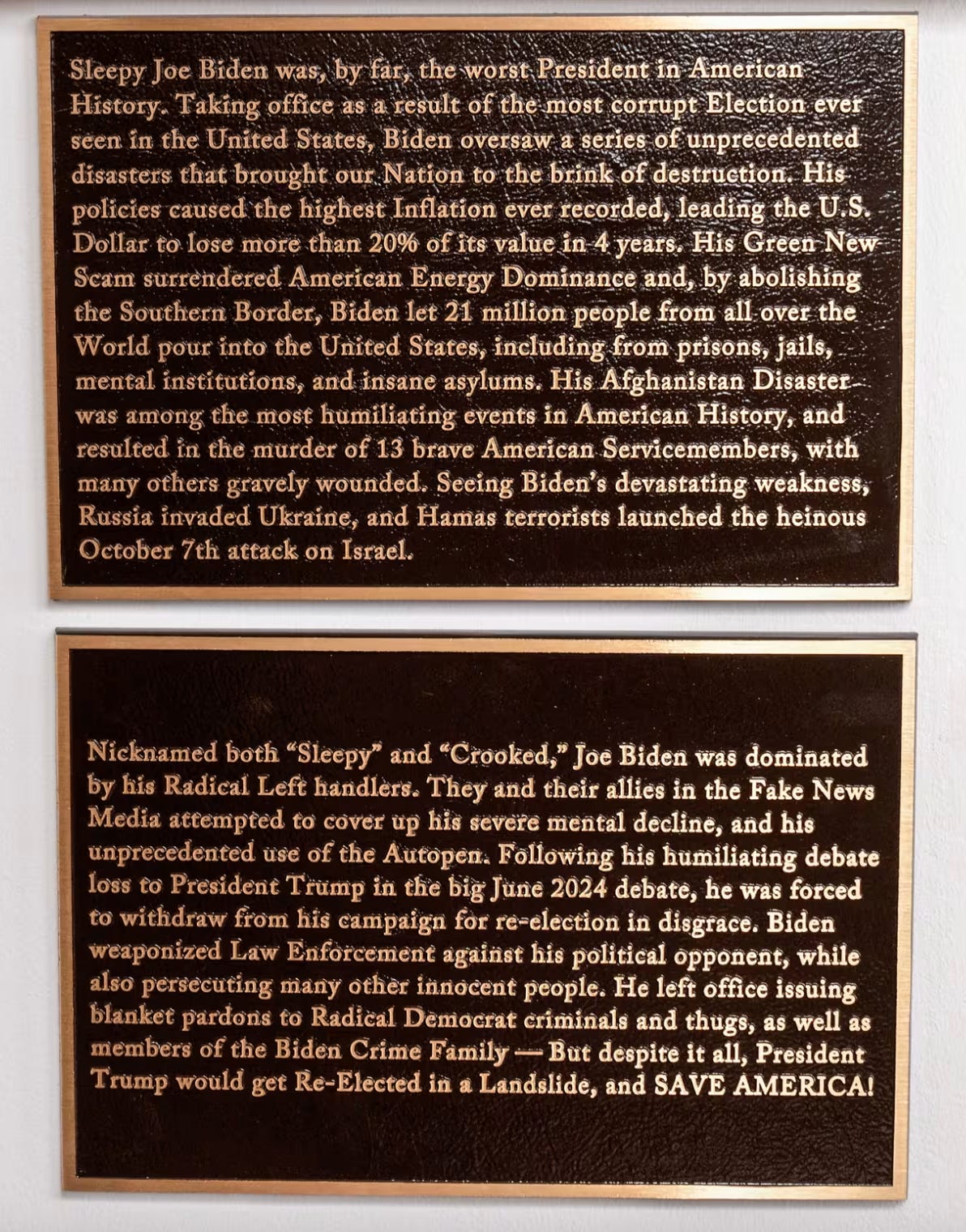

The White House unveiled a series of plaques near the Oval Office on Wednesday that mock President Trump’s recent Democratic predecessors in the style of his hyperbolic social media posts.

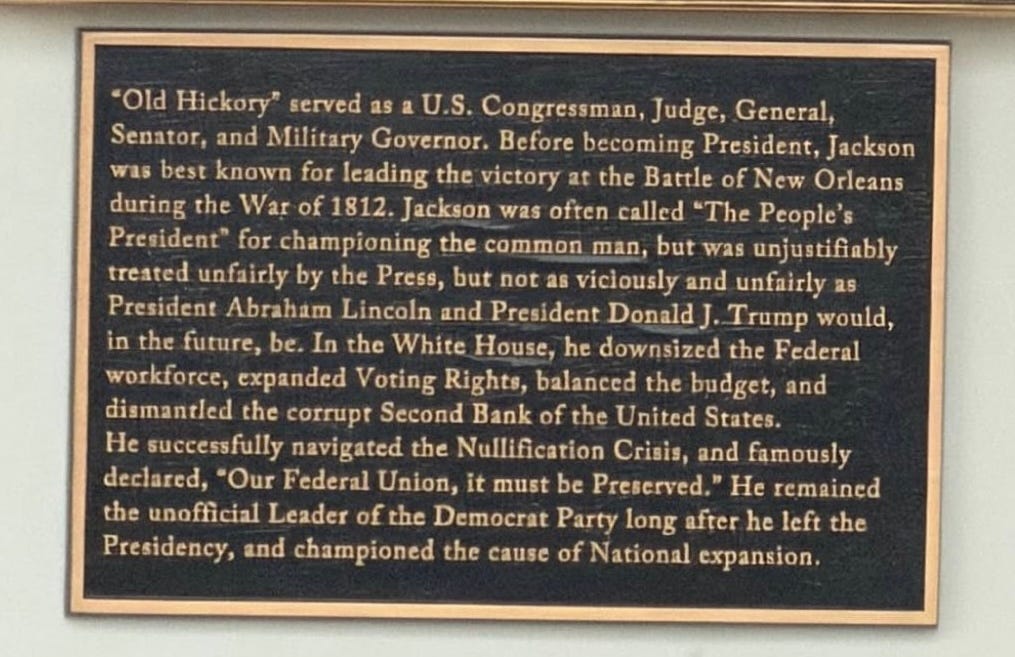

…. The exhibit, called the Presidential Walk of Fame, features every U.S. president, describing their records in office with varying levels of accuracy and fondness depending on their party affiliation and, apparently, Mr. Trump’s opinion of them. The descriptions become more pointed and partisan as they approach the current era. The plaque for Ronald Reagan, for example, declares that “he was a fan of President Donald J. Trump before President Trump’s historic run for the White House. Likewise, President Trump was a fan of his!”

Here’s the plaque for Joe Biden:

The plaque for Andrew Jackson positively references Trump in the same breath as Abraham Lincoln:

These stories honestly made me more sad than angry.

When I see these actions from Trump, I often think of the line from the otherwise forgettable Oliver Stone film “Nixon.”

“Can you imagine what this man would be like had anyone ever loved him?”

I also think back to a piece I wrote for the Boston Globe in 2020, reviewing Mary Trump’s book about her uncle’s crippling social pathologies.

When he was just 2, [Trump’s] mother suffered a serious postpartum infection and hemorrhaging that left her in the hospital for months and ailing for years. At a formative moment, when maternal attention and soothing is so crucial of childhood development, Trump was deprived of both.

According to the book, Trump’s father Fred Trump viewed children as a nuisance and child-rearing as a woman’s responsibility. He was cold and distant and rarely displayed emotion toward his kids.

This lack of attention, writes Mary Trump, led her uncle to “develop powerful but primitive defense, marked by an increasing hostility to others and a seeming indifference to his mother’s absence and his father’s neglect.” His emotional needs could not be met because he became “adept at acting as though he didn’t have any.” Trump’s bullying, aggressiveness, arrogance, and bouts of grandiosity — that we have all become inured to — are well-honed defense mechanisms that masked his lack of self-esteem, gnawing insecurities, and limitless need for validation. In perhaps the saddest sentence of the book, she writes that Trump “knows he has never been loved.”

… In Mary Trump’s telling, Trump is emotionally much the same person now that he was at 3.

Trump’s childhood trauma made him the person he is today. It’s why his horrendous response to the murder of Rob and Michelle Reiner was to make it about himself. He is not capable of viewing the world through anything but the prism of his own ego. And it’s why he feels the need to denigrate the presidents who came before him. Doing so makes him feel better about himself and soothes the voices in his head that tell him he’s inadequate.

A normal, healthy president would balk at the idea of renaming the Kennedy Center after themselves, because it looks so pathetically needy (not to mention inappropriate). But not Trump.

He is a pitiable figure with an unending need for validation. But since his ego is so damaged — and he is oblivious to anything but his own emotions — he doesn’t understand that his constant seeking of affirmation makes him look so sad and damaged.

Yet, that limitless hole inside him can never truly be filled. Even the momentary affirmation that comes with changing the name of the Kennedy Center is fleeting. Like a junkie, Trump is always searching for his next fix.

He’s just a profoundly and irretrievably broken person.

To be clear, I don’t expect any of you to feel sorry for Trump. Saving your empathy for those harmed by his policies is more than appropriate.

But recognizing Trump’s pathologies helps us understand that abuse, neglect, deprivation, and trauma can subvert our personalities in damaging and enduring ways that we cannot fully control (or even understand).

As I wrote five years ago:

The choices we think we, and others, make to be good or bad, are not so straightforward. This doesn’t mean that we don’t have free will or that people should not be held accountable for their actions. Rather it means acknowledging that life is far more complicated than the simple morality tales of good and bad that we tell each other and ourselves. It means creating room in our hearts for empathy and forgiveness, even for those who seemingly don’t deserve it.

We all bring a ton of baggage to the table. We’re all flawed, we all make mistakes, and we all are the products of our past experiences — for better or worse. I’ve long believed that one of our greatest gifts as humans is the ability to recognize our personal failings and seek both forgiveness and redemption. But I also understand that for some, like Trump, that isn’t possible. He is who he is, and he’s never going to change.

Nonetheless, even during this holiday season that has been so uniquely traumatic, I try to remember that creating room in our hearts for everyone, even for those who do and say terrible things, is the best way to preserve our own humanity.

One Battle After Another

This week on “That ‘70s Movie Podcast,” Jonathan and I went in a very different direction … we discussed the latest Paul Thomas Anderson movie, “One Battle After Another.”

Yes, we’re aware that it’s not a ‘70s film! And we don’t plan to make a habit of it, but we both were really intrigued by the movie and felt there was so much to discuss … so what the hell!

We talked about Paul Thomas Anderson’s legacy as a director, the influence of ‘70s cinema on his filmmaking, and how this film was a departure in form from his previous movies.

We praised the performances of Leonardo DiCaprio, Teyana Taylor, and Benicio del Toro, and also marveled at the movie’s combination of emotional depth and riveting action and chase sequences.

We poked a few holes in “One Battle After Another’s” occasionally cartoonish bad guys while discussing the film’s larger themes. Is PT Anderson mocking self-described revolutionaries, or instead offering a roadmap for those intent on producing political change? Is the film, at its core, a contrast between political workhorses and showhorses?

So please give it a listen and let us know what you think!

Check it out on Spotify and Apple Podcasts.

Musical Interlude

My favorite holiday songs!